Concordia Seminary Newsroom

A conversation…on Luther and the Reformation

Seminary professors Drs. Erik Herrmann and Paul Robinson recently sat down and discussed Martin Luther and the Reformation. Read a few excerpts from their conversation to help put the Reformation in perspective and learn more about Luther, his world and why the Reformation still matters — nearly 500 years later.

What was the Catholic church like at the time of Luther?

Robinson

“Many people were critical of the church in the late Middle Ages. Luther was not the first to criticize church practices. The dominant theology of the day taught that people had to amass good works in order to receive grace from God. You put your good works in, you got grace out. As a result, people looked for opportunities to do good works. Going to Mass became very important. Going to Mass did not necessarily mean receiving Communion. Parishioners received Communion only once a year. The Mass was about watching the priest celebrate the Mass and having that count as a good work. They were taught that the sacrifice was the important thing and by being there you could gain grace from God. It wasn’t necessarily to receive the elements.”

Herrmann

“It was a common phrase: ‘I went to see my Maker today.’”

Many people were calling for church reform. What made Luther’s appeal so much more significant and lasting?

Robinson

“Luther was one of the few people who went beyond criticizing the superstitions of the church and the piety to get at the roots of church teaching that led to these kinds of practices. He was the only one who went about it in this thoroughgoing and persuasive way.”

Herrmann

“For example, while everyone denounced priests and monks for fooling around and not keeping their vows of celibacy, Luther criticized the notion of celibacy as a pre-eminent state. He defined marriage as being more faithful to God. He critiqued the whole notion of monasticism and its vows. He went to the root of the thing. He didn’t just try to fix the practical problems.”

Robinson

“He did the same thing with Mass. Instead of just being critical of people’s practices of the Mass, he went to the heart of the matter and said ‘you people have turned the Mass into a sacrifice, into something we are doing for God when in fact it’s something God is doing for us and it needs to be completely re-understood in the light of the New Testament.’”

Herrmann

“Luther took the pieces that he found helpful throughout the tradition and connected them in a way that reformed what it means to be a Christian. Luther was the catalyst who set the agenda for all other reform movements in the 16th century including the Catholic church. He said the true treasure of the church is the Gospel. True religion is faith not works.”

Some historians say Luther didn’t nail the 95 Theses to the Castle Church doors in Wittenberg, Germany, but rather mailed them, your thoughts?

Robinson

“We don’t have a definitive answer. The first time it’s mentioned is many years after the fact in Philip Melanchthon’s funeral oration for Luther. That doesn’t necessarily mean that it really didn’t happen. But if it did happen and Luther meant it is a gesture of some sort, I think he would have written about it the way he did the burning of the papal bull excommunicating him. What we do know is that he sent the theses out to others.”

Herrmann

“I suppose you could safely say, ‘Whether he nailed it or mailed it, he definitely posted it.’”

What was Luther’s goal in posting the 95 Theses?

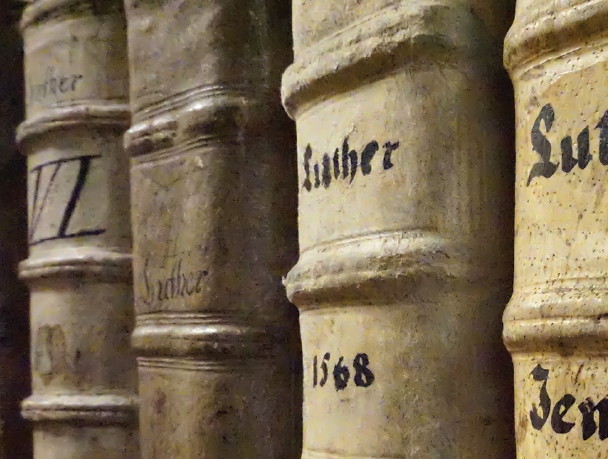

Photo: Harold Rau

Herrmann

“It was modest. His goal was to reform the practice of a kind of preaching that kept people from reflecting on their sins and trying to be better. He wanted people to think about true repentance and what it means to be a Christian, what it means to be a sinner before God. An indulgence short-circuited the whole thing: You don’t have to feel bad about your sins; you just pay a little fee and then you’re done.”

What is the significance of the 95 Theses?

Herrmann

“They are not some Lutheran manifesto. If people want that, they have to read something from later in Luther’s life. What they are is a very traditional criticism of the preaching of indulgences without really attacking the fundamentals of indulgences directly. They suggested that the pope didn’t have the authority to extend indulgences to people in purgatory, for example.”

Robinson

“Maybe the one thesis [of the 95 Theses] that people should know is the first one: ‘When our Lord and Master Jesus Christ said repent, He meant that the entire life of the believer should be one of repentance.’”

Herrmann

Luther’s whole theology can be seen in light of that: a life of repentance. From Luther’s thinking, if you want to reform the church, you have to reform the way theology is taught and that will trickle down into preaching.”

How important was the printing press to the Reformation?

Robinson

“Luther’s ideas spread rapidly and far because of the printing press. He purposely embraced this technology for his cause.”

Herrmann

“Suddenly, for Luther, the printing press led to enormous industry. The amount he wrote in three or four years was enormous. Something like a third of all the printings in Germany by 1520 were written by Luther.”

If Luther were alive today, what would he think about the Reformation’s impact on Christianity?

Robinson

“I think he would be very happy to see all of the different versions of the Bible in different languages. At the same time, he’d be upset that more people don’t actually read it, which was always the problem. But I also don’t think he would expect to come into a 21st century world and see a church that is exactly like it was in 16th century Germany.”

Herrmann

“If you viewed church the way Luther viewed it — God’s people around His Word — there’s a certain expectation that Christianity will look different from place to place. It wasn’t a goal to have one formal church that looks exactly alike. He did not define church that way.”

Robinson

“Luther essentially asked Christians to do a very difficult thing; to live as church in a way that keeps the Gospel at the center and demonstrates freedom in the Gospel.”