Concordia Seminary Newsroom

Beyond a Mirage

by Dr. Peter Nafzger

The Christian life is always lived in community. When God calls people to faith in Jesus, He also gathers them together for life with other believers. Martin Luther understood this. In his explanation to the Third Article of the Apostles’ Creed, he would not finish his sentence about the Spirit calling individuals without insisting that the Spirit also gathers the whole Christian church on earth. As I used to tell my congregation in Minnesota, it is impossible to be a Christian alone! By faith we are members of one another (Rom. 12:5); we are baptized into one body (1 Cor. 12:13); we share one Spirit, one hope and one Lord (Eph. 4:4-5). We get a glimpse of this communal life every Sunday morning. Yet even at church, the experience of authentic community can be hard to find. One of the paradoxes of the Christian life is that we are at the same time saints and sinners. That is, we are the people God has made us to be … and at the same time we are not. With respect to Christian community, we are at the same time perfectly unified and yet also hopelessly separated and separating. Most of us have experienced this paradox firsthand. We have attended congregations that share spaces, songs and Sunday morning schedules. But we don’t feel like we belong.

Community strategists Carrie Melissa Jones and Charles Vogl suggest that authentic community is more elusive than it may seem. Many groups aspire be a community, and many groups call themselves a community, and many groups look like a community to outsiders. But beneath the surface lurks division, disengagement or indifference. Jones and Vogl call such groups “mirage communities.” The appearance is an illusion. In contrast to mirage communities, Jones and Vogl suggest that authentic community requires three fundamental characteristics: (1) members participate in shared experiences; (2) these shared experiences are grounded in shared values; and (3) these shared values and experiences are lived out through mutual love and concern for one another’s welfare.

At Concordia Seminary, St. Louis we recognize the communal nature of the Christian faith. With Luther, we believe, teach and confess that God calls and gathers us together. As Seminary Emeritus Professor Dr. Robert Kolb puts it, God is a “God of conversation and community.” He provides community as a gift and we receive it (on good days) with joy and thanksgiving. But we also understand there are centrifugal forces in our culture and in our selfish hearts that drive Christians apart and undermine our life together. For this reason Christian community cannot be taken for granted. Congregations and synods and seminaries must work hard to avoid becoming mirage communities. That is why our recently adopted strategic plan names “Commitment to Community and Collaboration” as a top priority of the Seminary.

This sounds good. But what does it look like? How does a seminary embody a “commitment to community and collaboration”? Jones and Vogl’s three characteristics are helpful.

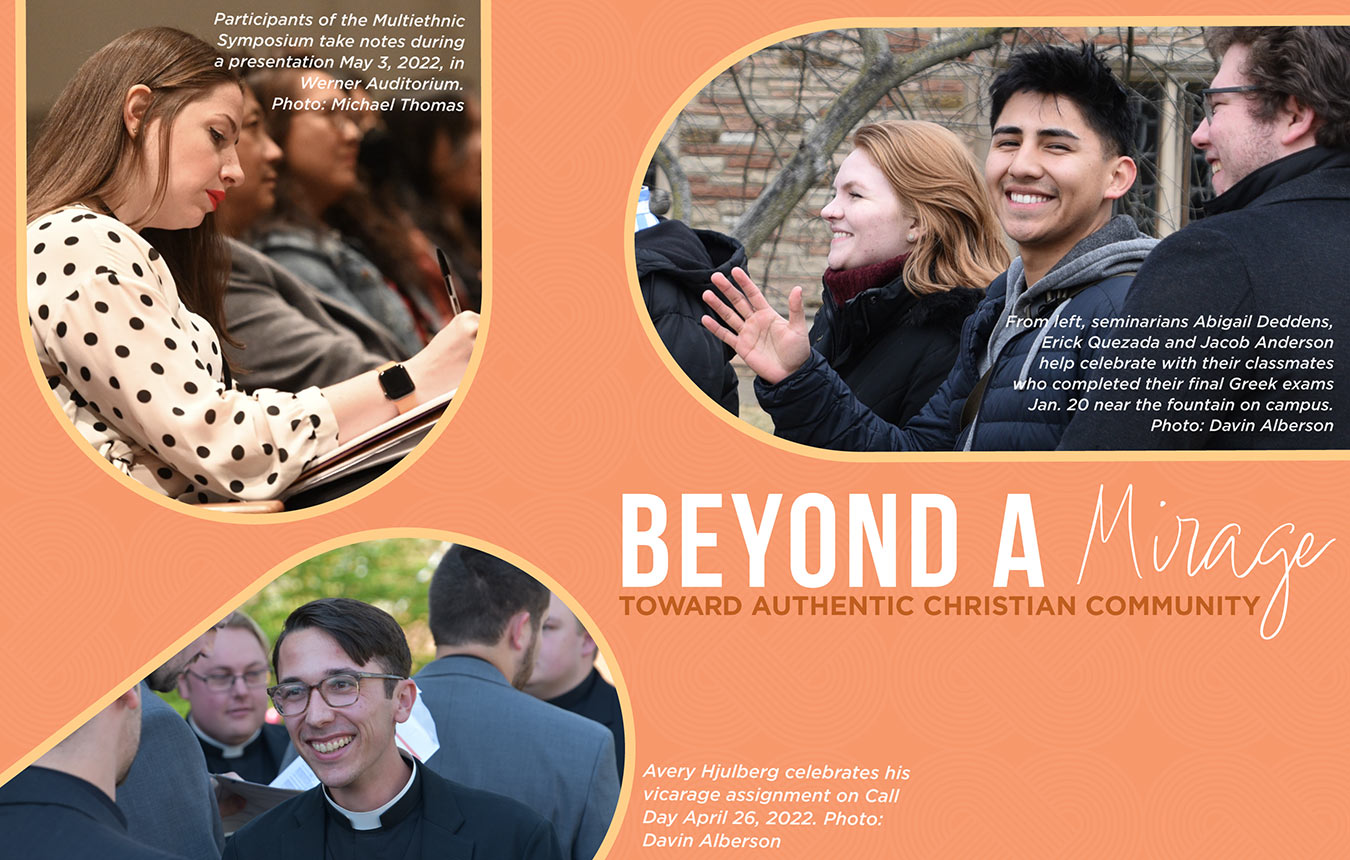

Let’s start with shared experiences. Shared experiences at Concordia Seminary come in many shapes and sizes. They happen most regularly in the classroom and in chapel. There we gather to learn about Jesus and worship in His name. But our shared experiences extend much further. They include intramurals and Life Team events, Prof ’n Steins and after chapel coffee, Friday night basketball games and annual celebrations of Bach’s birthday. Visit campus and you will find impromptu gatherings in the library and in the dining hall, at the playground for our students’ children and on faculty home patios, around the fire pit and by the grill. These shared experiences do not automatically create community. But they provide the atmosphere for community-building conversations to take place.

These shared experiences flow from shared values. At their most basic, these values could be narrowed down to two: love of God and love of neighbor. While no one at Concordia Seminary is perfect, we are all here because we love that He first loved us (1 John 4:19), and we love helping and serving others. As a professor, I get to witness students’ love for God and for others on a regular basis. For example, this semester I am teaching an elective called “Confirmation and Christian Formation.” In this course we take a close look at the history and development of confirmation as a church practice; we face with honesty the alarming statistics about the church’s struggle to retain youth in an increasingly post-Christian culture; and we discuss potential improvements that would lead to a more faithful Christian formation in the future.

Most students in this class are only months away from their first call. Their love for the young people in their future congregations (whom they have not yet met) is palpable. They believe the church can do better, and they eagerly engage in substantive conversations about how to make it happen.

Shared experiences and shared values are essential. But the experience of authentic community requires one more: mutual love and concern for one another’s welfare. This gets to how we are with one another. And this is what makes Christian community stand out as distinctively Christian.

It is easy to care for those who think like you think, who share your perspectives and who do right in your eyes. “Even sinners do that,” Jesus said (Luke 6:32-34). So does our world. But outside the church, love and concern for the welfare of others is like the morning dew that vanishes with the rising sun. Disagreements are met with displays of force. Hurt feelings are dismissed as necessary casualties. Mistakes are covered up with faux apologies.

Christians, however, do things differently. Christians count others more significant than themselves (Phil. 2:3). Christians bear with one another in love (Eph. 4:2). Christians forgive as we have been forgiven (Col. 3:13). My colleague Dr. Timothy Saleska, a professor of Exegetical Theology at the Seminary, often reminds us that we are “Gospel-centered people.” Which means we are “grace-centered people.” When disagreements arise, we do not become disagreeable. When we reach an impasse, we don’t come to blows. We love without judging. We listen to one another with compassion. We put the best construction on everything. We are quick to forgive, and we are eager to maintain unity in the bond of peace.

This doesn’t come naturally, of course. Not to our sinful nature. So here on campus we practice these things. We have Confession and Absolution — daily. We hold one another accountable in personal formation labs — every week. We gather to laugh and share our stories at social events on campus at least once a month. We continually remind one another that we are baptized members of the risen Lord Jesus, and this means we are no longer our own. We belong to Him and we are in this life together. This is the way of Jesus. Therefore it is our way, too.

Mirage communities are easy. Authentic community is not. It requires effort, patience and humility. Like any congregation or church body, Concordia Seminary is not perfect. But we recognize the communal nature of our life in Christ. And we are committed to making it happen. So we create opportunities for shared experiences. We are dogged about naming and celebrating our shared values. We foster Christian habits that support genuine love and concern for one another’s welfare.

In other words, we strive to become the community of believers that the Spirit has already made us to be. Not for our sake alone, but so that our students may do the same for the congregations they will soon be called to serve.

Dr. Peter Nafzger is associate professor of Practical Theology and director of student life at Concordia Seminary, St. Louis.